Grayson Perry vanity identity sexuality

The Monnaie de Paris is organising the first major solo exhibition in France by the celebrated British artist Grayson Perry (born 1960, lives in London). Perry’s works in traditional materials such as ceramics, bronze, cast iron, printmaking and tapestry, offer an ironic and darkly humorous look at universal topics such as identity, gender, class, religion and sexuality.

Perry’s honest and candid unpacking of his own identity is part of what drives his appeal far beyond the confines of the art world. Autobiographical references – to the artist’s childhood, his family and his transvestite alter ego Claire – can be read in tandem with questions about décor and decorum, class and taste, and the status of the artist versus that of the artisan.

In several of his works he challenges traditional masculinity and demonstrates how its values and traits have been eroded. These themes are further explored in his book The Descent of Man (2016), in which he explores the ways in which rigid masculine roles can be destructive and suggests an upgrade of masculine identity.

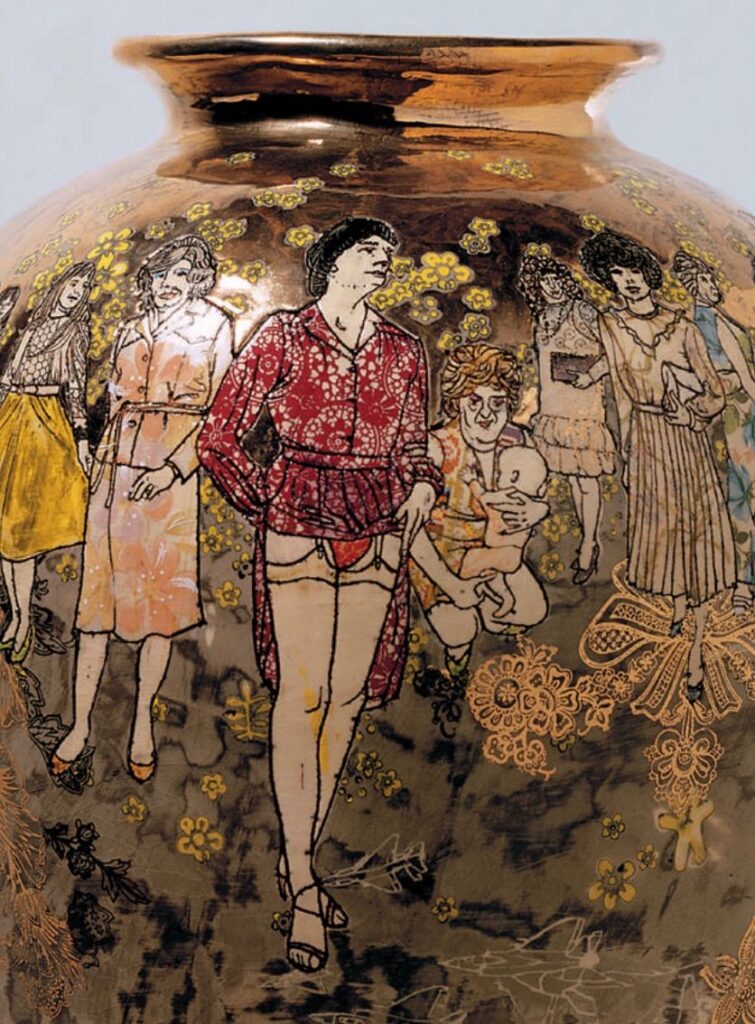

The winner of the Turner Prize in 2003, Perry made his name with his ceramic works, which he began in the 1980s at a time when ceramics were little considered in the contemporary art world. Covered with sgraffito drawings, handwritten and stencilled texts, photographic transfers and rich glazes, Perry’s detailed pots are deeply alluring. Only when we are up close do we start to absorb narratives that might allude to complex subjects, and, even then, the narrative flow can be hard to discern. He uses the seductive qualities of ceramics and other art forms to communicate his thoughts on society.

Included in important national collections (Tate Collection, UK, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, Museum of Modern Art, New York), Perry’s work has been exhibited widely in the UK

(including The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman at the British Museum in 2011–12; and The Most Popular Art Exhibition at the Serpentine Galleries in 2017) and internationally (including Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht, the Netherlands and ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, Denmark, in 2016).

Invited to coordinate the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts this year, he also writes and presents a series of television programmes for Channel 4 on the themes explored in his art, such as the crisis of masculine identity and the taste and idiosyncrasies of the British.

The exhibition will occupy the two floors of the Monnaie de Paris and be divided into ten themed chapters that reveal the artist’s interests.

The Monnaie de Paris has wanted to show its support for equality in art and investigate the concept of gender since 2017. Following the success of the exhibition Women House, the Monnaie de Paris is pleased to welcome Grayson Perry, an openly feminist artist and the theoretician of a new role and place for men in society. The link between his practice and the expertise of the craftsmen of the Monnaie de Paris will be highlighted by a dialogue between tradition and modernity, in particular the creation of a new medal designed by the artist and made by the mint. A selection of religious medals and collectors’ objects linked to British history created by the Monnaie de Paris will be presented with the works of Grayson Perry and his iconographic sources.

The exhibition is being produced in partnership with the Kiasma Museum of Helsinki and with the support of the Victoria Miro gallery in London. It will be organised by Lucia Pesapane, curator at the Monnaie de Paris, as part of the arts programme devised by Camille Morineau, the Exhibitions and Collections Director.

Grayson Perry Bio

Born in Chelmsford, Essex in 1960, Grayson Perry lives and works in London. The Most Popular Art Exhibition Ever! was on view at Serpentine Galleries London, during the summer of 2017, travelling subsequently to Arnolfini, Bristol. Institutional venues for other solo exhibitions include ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, Aarhus (2016); Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht (2016); Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney (2015 – 2016) and Turner Contemporary, Margate (2015). In 2011, The British Museum opened The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman, a show in which Perry combined his own works with historical artefacts chosen from the British Museum collection.

The Vanity of Small Differences is a monumental suite of tapestries exploring the subject of taste in contemporary Britain. The making of these works was chronicled in the first of Perry’s Channel 4 television series, All In the Best Possible Taste, a 2013 Bafta Specialist Factual winner. Perry’s second Bafta-winning television series Who Are You?, about identity, was broadcast in 2014, accompanied by a solo presentation of works at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

The series All Man, which considered masculinity, followed in 2016, with Allen Lane publishing the related book The Descent of Man. Perry delivered The Reith Lectures, BBC Radio 4’s annual flagship talk series, in 2013; his ensuing book Playing to the Gallery is published by Penguin. The artist’s A House for Essex, a permanent building designed in collaboration with FAT Architecture, was constructed in the North Essex countryside in 2015.

Work by the artist is held in museum collections worldwide, including The British Museum, London; Tate Collection, London; Bonnefanten Museum, Maastricht; Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; Stedelijk Museum; Amsterdam; Victoria & Albert Museum, London and Yale Center for British Art, New Haven.

Winner of the 2003 Turner Prize, Perry was elected a Royal Academician in 2012, and received a CBE in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List in 2013; he has been awarded the prestigious appointments of Trustee of the British Museum and Chancellor of the University of the Arts London (both in 2015), and received a RIBA Honorary Fellowship in 2016.

Grayson Perry exhibition plan

identity

I realised that being a transvestite wasn’t about pretending to be a woman. It was about me putting on the clothes that gave me the feelings that I wanted. Further to the definition of gender and the notion of identity, Grayson Perry’s art questions the masculine/ feminine divide with works that take us beyond appearances and prejudices. Menace and hatred can hide behind words such as ‘normal’ or ‘natural’ which blind us to the broader perspective. The works featured in this chapter propose alternatives to the dominant heterosexual model and sketch the outlines of a society without norms, free from traditional gender roles. Endeavouring to raise awareness of these issues, Perry suggests a restructured value system and asserts the right to be different. With his vases, sculptures and wall ceramics, he revives and references ancient artistic traditions, such as West African bronzes, for example, or the taste for floral decoration and calligraphy.

masculinity

When talking to men about masculinity, I often feel I am trying to talk to fish about water. Men live in man’s world, they are unable to conceive of an alternative. […] they feel feminism is an attack on their core identity, rather than a call for equality. Much of Grayson Perry’s work challenges the masculine ideal and shows how it has been eroded. In the artist’s view, illustrated by the selection of works on display here, men have lost their bearings and sense that their privileges are under threat; the job crisis has robbed them of their role as head of the family and unemployment has stripped them of their professional status. The undermining of the traditional model of male dominance, based on physical and moral strength and sexual power, has resulted in anger and frustration, manifested in increasingly violent behaviour – and sometimes even in suicide among young men. Perry’s redefinition of roles promotes equality and sharing and advocates a more flexible masculinity which would allow men to lower their defences, admit their fragilities and express their feelings at last.

new masculinity

We all learn to be men from our fathers. Taking a sociological approach, Grayson Perry uses his art to study the ways in which the male temperament is created, revealing the extent to which boys are socialised by their fathers – their models, mentors and critics. From the age of four, the artist began to construct a masculine ideal other than the father figure. During his childhood with a volatile mother, he lived in constant fear of his bullying stepfather and dreamed of a less aggressive, more empathetic man. He projected all the latter’s positive qualities onto his teddy bear, Alan Measles (Alan was his best friend’s name, and Perry had measles at the age of three); this teddy sits behind the artist on his customized ‘popemobile’ motorcycle. A frequent figure in Perry’s art works, Alan is sometimes depicted as a conquering hero, sometimes as a god or an elderly sage. The artist uses his teddy bear as an example of how to exchange the dominant model of masculinity for an alternative model that’s ‘easy to park, with a big trunk, child seats and low fuel consumption.’

hospitality

The referendum was never about staying in Europe or not, it was about one group of people with one set of cultural values opposing a group of people with another set of cultural values.

During the three years that elapsed between the production of Perry’s two tapestries entitled Comfort Blanket and Battle of Britain, British society underwent a major upheaval. On June 23, 2016, the referendum on whether Britain should remain in the EU led to an earthquake that severely undermined the concepts of nationhood and shared values. The brightly coloured Comfort Blanket shows the welcoming face of pre-Brexit Britain; the landscape depicted in Battle of Britain is contrastingly gloomy. The works reflect a country in crisis, split in two between urban and rural voters, people who have reaped the benefits of globalisation and people who haven’t, baby boomers and millennials.

The two large pots entitled Matching Pair illustrate the same theme. They were created following an appeal by Perry through social media, when he invited the public to contribute ideas, images, phrases and photographs to represent the things people loved about Britain, their favourite brands, who represented their values and their thoughts about Brexit.

The two resulting works, one representing the (proBrexit) Leavers and the other the (anti-Brexit) Remainers in fact look remarkably similar. Perry shows how the British have far more in common than that which divides them, suggesting that the vote was an emotional rather than a rational or financially motivated reaction to a changing society.

historicity

Makers of artefacts have been ‘responding’ to objects made by earlier generations since the beginning of craft. I think of the history of culture as an infinitely complex game of ‘Chinese whispers’, where images and ideas are changed by passing through the hands of various craftsmen. Filtering them through a series of personal experiences, each idea becomes something new, not necessarily because of some revolutionary inspiration but because creativity is often a series of innocent mistakes.

Medals may be discreet artworks in terms of size, but the images and messages they convey can have extraordinary historical, political, religious or social resonance. Medals testify to the moods of peoples and nations, glorifying or lamenting military exploits, honouring the worthy or deriding the undeserving, encouraging or ridiculing religious belief, recording or making light of serious events. Medals have been a forceful and moving means of expression since the Renaissance; when they have a social or political role, the narrative power of contemporary medals can be used to idolize, revere, condemn, provoke or unsettle.

Attentive to these paradoxes, in 2008 Grayson Perry designed a medal called For Faith in Shopping. Drawing inspiration from satirical medals and the religious iconography of processional Madonnas, he turned his sardonic wit to the consumer society, its excesses, injustices and taboos.

The selection of medals from the heritage collection of the Monnaie de Paris was chosen to resonate with Perry’s artistic, sociological and quasi-anthropological observations of British society. Medals struck or cast in the late 19th and second half of the 20th century echo some of the artist’s favourite subjects, illustrating British history, religion and society from the Middle Ages to the present day – its rulers, saints, intellectuals, artists and scientists.

antiquity

People still come to museums to see the actual thing made and touched by craftsmen and marvel at their skill.

Grayson Perry spent four years exploring the British Museum’s collection in preparation for his exhibition held there in 2011, entitled ‘The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman’. Combining the artist’s own works with artefacts from the museum, the exhibition took visitors on a pilgrimage through the centuries and paid tribute to the unknown men and women who have produced these treasures since ancient times. The choice of works, guided by the notion of craftsmanship, reflected Perry’s interest in ancient art. Inspired by African or Asian sculptures, Our Father and Our Mother represent pilgrims on a spiritual quest – and today’s migrants, forced to flee their homes in search of a new land, burdened by memories of their pilgrimage and the objects they chose to keep when they fled. Perry began by making terracotta figures; moulds were made from these to produce metal figurines which were then painted to create a rusty look and an ancient-looking patina.

The artist’s maps of imaginary places were inspired by the Ebstorf mappa mundi, one of the most famous 14th century world maps. Like Perry’s maps, the medieval mappa mundi is more than a mere representation of places; it also contains a vast collection of data in the form of texts and images. Medieval maps reflect the historical, mythological and theological knowledge of the time; Perry’s illustrate his own system of value.

I am a transvestite so I have always questioned our attitudes to sex. In contemporary society there is much anxiety about the sexualisation of our culture, but sexual imagery has always been around.

Many of Perry’s early works reflect his fascination with the diversity of sexual practices and fantasies. His images of (usually male) genitalia represent both a caricature of virility and a satire of British society’s deeply rooted sexual taboos. After setting out to shock and provoke, his approach evolved over time with works that retained a sharp and incisive tone but began to touch on a far wider range of themes. The ornate decoration of the type of vases on display here and the black outlines of the drawn figures recall Fauvist ceramics, which inspired this colour-loving artist whose graphic style is also reminiscent of comic book art and illustrations by outsider artists like Henry Darger.

society

Part of the reason we choose to consume culture is how it might reflect on our status.

Grayson Perry uses the appealing qualities of glazed ceramics and other art forms to explore a wide range of historical and contemporary issues and deliver an incisive critique of society, with its pleasures, flaws and inequalities. Some of the works on display in this section, for example, target the shifting fashions and fads of the consumer society.

Perry is a popular and politically engaged artist, an active contributor to the public debate. He uses his special insight into his country to crack its cultural code with a typically British sense of humour. The large pot, Queen’s Bitter, for example, is covered in patriotic imagery, with drawings completed in a deliberately folk-art style. The headscarf carried by the artist represents one of the last vestiges of polite clothing and of a dying Victorian civility. It may raise also the question of the Islamic headscarf and, more generally, prompts a reflection on the concept of secularism. Other pots feature historical figures such as Jane Austen (who, like Perry, was renowned for her realism, biting social commentary and original humour) alongside scenes of urban violence inspired by contemporary life on the outskirts of London.

divinity

When I had the idea to build a house I wanted it to be like a religious building : one of the good things about religions is that they have a big narrative; I like spirituality when it touches a definite story.

After five years’ work, the collaborative project between Grayson Perry and the FAT Architecture firm was completed in 2015. Covered in ceramic tiles and decorated with tapestries and sculptures, ‘A House for Essex’, in the Essex countryside, covered in ceramic tiles and decorated with tapestries and sculptures, can be rented for short breaks. Designed as a ‘modern Taj Mahal, a chapel to Julie and all ordinary women’, the house is an architectural mix: part Scandinavian church; part Thai temple. The ‘Julie Cope’ to whom it is dedicated is a character invented by Perry, whose fictional life story involves an early marriage, children, divorce, remarriage, then an untimely death in a brutal road accident. The large-scale tapestry records part of her life – a largely happy one with its share of joy and suffering, triumph and failure. A celebration of ordinary heroism, Perry’s chapel is dedicated to women in general, whom he considers better able than men to create a fairer, more egalitarian society.

vanity

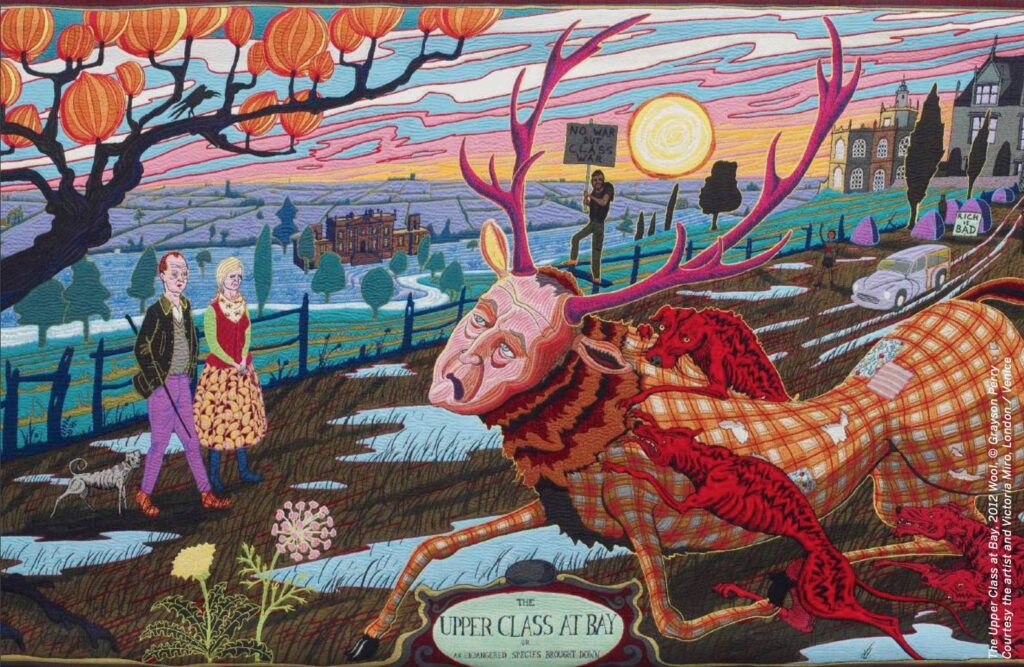

I wanted to research a series of artworks about class and taste. I thought it would be refreshing to use tapestries – traditionally status symbols of the rich – to depict a commonplace drama: the drama of social mobility.

Grayson Perry has been working with tapestry since 2009. Rather than large mythological scenes or historic battles, his works show the peculiarities and eccentricities of life in modern Britain; the artist uses this ancient allegorical form to portray the social differences and divisions that continue to pervade British society. For his series entitled The Vanity of Small Differences, the artist drew inspiration from A Rake’s Progress (1733-1735), a series of eight canvases by the famous British painter William Hogarth.

Based on Hogarth’s character Tom Rakewell, Perry’s tapestries tell the imaginary tale of a character called Tim Rakewell, from birth to death: his childhood in a working-class, single-parent household; his emancipation through education; his lucrative career in software development; his untimely death. The story’s main thread is the young protagonist’s progress through the social strata and tastes of modern British society.

The titles and compositions of Perry’s tapestries recall Italian Renaissance religious paintings, while the title, The Vanity of Small Differences, derives from Freud’s concept of the ‘narcissism of small differences’ – an allusion to our desire to demonstrate our individuality by distinguishing ourselves from members of the same social group

Oct 19 2018 - Feb 3 2019