Anne and Patrick Poirier Romamor exhibition at Villa Medici

Anne and Patrick Poirier are one of the international art scene’s most famous couples. Their creative symbiosis crystallized here at the Villa Medici in Rome more than fifty years ago: a kind of archeology driven by the test of time, the traces and scars of its passing, the fragility of the things humans build, and the power of ruins ancient and recent.

All this in a spirit combining play and imaginative melancholy.

Anne was born in 1941, in Marseille. Patrick in 1942, in Nantes. The striking thing about their oeuvre is the mark it bears of the violence of the time they have lived through. From their earliest years these two artists have been confronted with war and devastation: Anne beginning with the bombing of the port of Marseille, Patrick with the death of his father during the destruction of central Nantes in 1943.

Both winners of the Rome Prize in 1967 after studying at the School of Decorative Arts in Paris, Anne and Patrick Poirier stayed at the Villa Medici from 1968 to 1972, at the invitation of Balthus, director at the time. That was when they decided to embark on the collaborative artistic adventure that led to the works bearing their dual signature.

Part of the generation of artists who began traveling and taking in the world in the 1970s, Anne and Patrick Poirier became fascinated by ancient cities and settlements, and more especially by the process of their disappearance.

Out of this distinctive sensibility emerged mysterious cities, imaginary archeological recreations, a passion for ruins, investigations of the nature of gardens, and a blending of historical works and site-specific creations. These are the sources for the ROMAMOR exhibition at the Villa Medici.

Their first major joint work, Ostia Antica (1969), was a terracotta model born out of their wanderings in the ancient port of Rome, which for them was an iconic archeological site. From there on in, their strivings after the traces of a historic past often led to an experiencing of absence embodied in the destruction of buildings and of the signs and heritages of earlier civilizations.

As they themselves say: “Periodically, then, we move from shade to light, black to white, order to chaos, ruins to utopia, past to future, introspection to mental projection. Our dual architect/archeologist identity means we can shuttle back and forth between these seemingly distant worlds in search of their secret interconnections.”

The Villa Medici exhibition welcomes the visitor with La Palissade/Scavi in corso (2019), which leads to a vision of ruins: the cistern of Finis Terrae (2019), illuminated by the neon declaration of A world that blows itself up won’t let us paint its portrait anymore(2001).

Then comes the first room and the luminously magical sculpture Le monde à l’envers(The World Upside Down, 2019): a globe of the world and celestial constellations, rounded off by a self-portrait of the artists as Janus, god of beginnings and ends, turned towards the future as he looks back towards the past. An ambivalent work, a manifesto to be viewed in counterpoint to the tapestry Palmyre (Palmyra, 2018) and its rendering of the site in Syria destroyed by ISIS in 2015.

The focal point of the next room is the Poiriers’ mythic L’Incendie de la grande bibliothèque (The Burning of the Great Library, 1976): a charred architectural metaphor for memory and the brain and its functioning. Part disaster and part utopia, part history and part founding myth, this sculpture confronts the beholder with the fragility that so often permeates the works of Anne and Patrick Poirier.

Inspired by ancient sites, the “city in the sky” that is Ouranopolis (1995) awaits in the following room. Anne and Patrick Poirier speak eloquently of their love of libraries as memory-metaphors that lead them to construct ideal museum-libraries: in this instance an elliptical building we can imagine taking off for other worlds with its harvest of memory at the least sign of impending disaster.

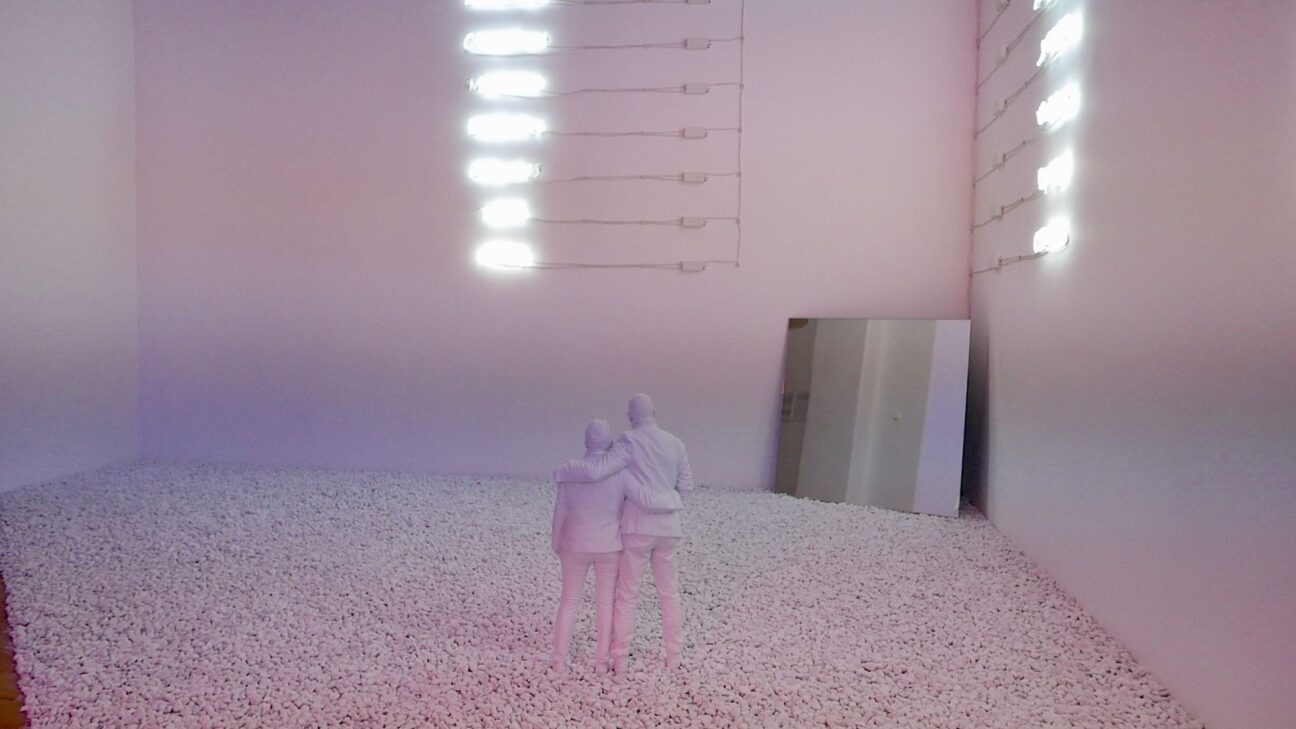

The luminous, dreamlike space glimpsed through portholes is on the main staircase of the Villa’s old stables, with the visitor precipitated into a “disturbing unreality”. Le songe de Jacob (Jacob’s Dream, 2019), composed of names of constellations, phosphorescent ladders, suspended snakelike shapes, and white feathers on the staircase accompany visitors step by step until they reach the pristine whiteness of Rétrovisions (2018), a self-portrait of the couple seen in a mirror, surrounded by a dazzling utopia of neon words.

A little further along is Surprise Party (1996): a deflated, bleached-out globe of the world sitting on an old, stridently scratchy record-player sitting, in turn, on a suitcase (another key part of the Poirier vocabulary)—a kind of nomadic geography, “a world out of kilter, a creaky planet.”

In a context of ongoing disorientation visitors are faced with Dépôt de mémoire et d’oubli (Storehouse of Memory and Oblivion, 1989): a crucifix made up of paper imprints of masks of ancient gods.

Lost Archetypes (1979) offers the eye the reconstruction on a human scale of major architectural complexes: a series of four white models of ruined sites. Past, present and future, collapse, construction and elevation: Anne and Patrick Poirier destabilize the Roman public’s historic landmarks.

In the next room, the collages: vegetal drawings captured in wax. Journal d’Ouranopolis (Ouranopolis Diary, 1995) is an attempt to combat oblivion—the destruction of memory. This intimation of a world ruled by vulnerability recurs in the images of Fragility and Ruins (1996).

The exhibition continues in the Villa Medici gardens. In Le Labyrinthe du Cerveau (The Labyrinth of the Brain, 2019) on the piazzale, the artists have drawn the shape of the brain, with its two hemispheres, in Carrara marble: a “bicephalous autobiographical manifesto”, a meeting of their minds, and a symbol of the themes—the mechanisms of time’s passing—they have been indefatigably exploring for more than fifty years. Their constructions are enormous brains, landscapes to be circled. As they are fond of saying, “The image of the brain and its two hemispheres could very well stand for us, representing both the unity and diversity of our symbiosis.”

Continuing on their way, visitors might imagine taking a break on the monumental granite Siège Mesopotamia (Mesopotamia Seat, 2012–2015) that so forcefully holds pride of place.

Further along, in the Fountain of the Obelisk, you can contemplate Le Regard des Statues(Gaze of the Statues, 2019), anonymous plaster eyes distorted by the water they are immersed in. Eye gazing at the sky and at time, the eye of memory and forgetting, the eye of history and violence leading to Balthus’s Studio and a mythic work created here at the Villa in 1971: paper stelae made from moldings of the Herms, those strange creatures the artists came upon in the gardens, shown together with “notebooks of personal reflections and drawings” and porcelain medallions bearing these funerary images.

The word that vivifies the exhibition, ROMAMOR (2019), appears in luminous red under the portico of Balthus’s Studio: a tribute to a city that has been of such importance to these two artists in both artistic and human terms.

IN Places city guide

until May 5, 2019